Impact of dementia

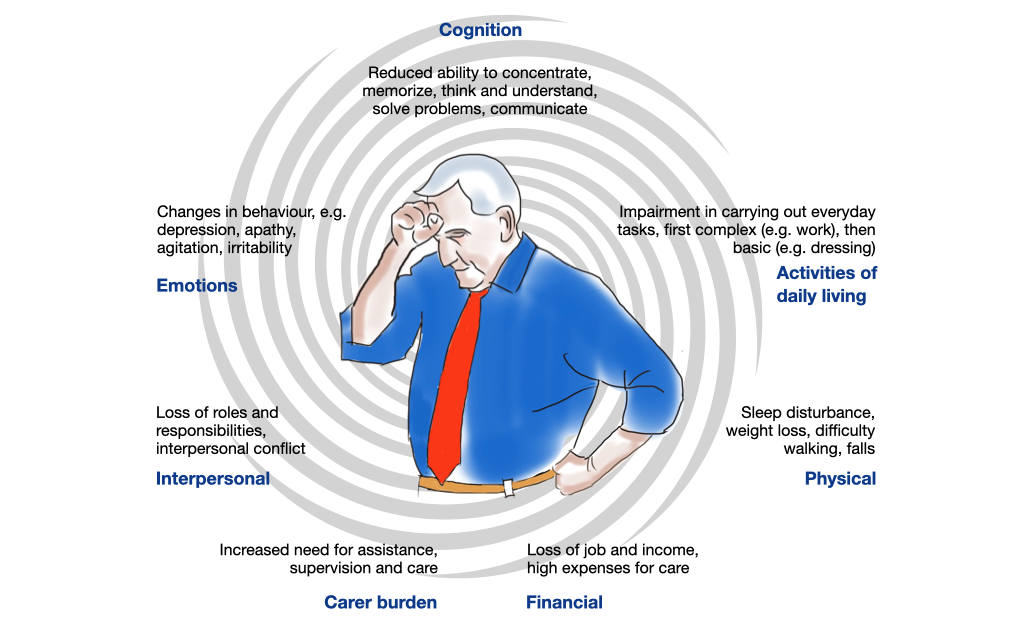

What does it mean when cognitive abilities decline, when everyday tasks become increasingly more difficult and when personal relationships shift - for people with dementia and for those directly around them?

Dementia has a profound impact on those affected and the people around them. Healthcare professionals can provide better support if they understand the experiences of people with dementia and their loved ones. The challenges begin even before diagnosis and require a holistic view that goes beyond medical symptoms.

Personal impact of dementia

Emotional consequences:

Dementia symptoms can trigger psychological defense mechanisms such as denial, trivialization and shock in order to relieve stress on the self. The diagnosis can trigger anxiety, depression and despair. However, it can also bring clarity and relief. Support in coping with these emotional challenges is important.

Self-esteem:

Reduced ability to cope with tasks, changes in roles and loss of self-esteem are understandable reactions to dementia. Public stigmatization of cognitive impairment worsens the situation.

Personal identity:

Personal identity is based on memories, social interactions and current activities. As dementia progresses, these sources gradually disappear, and the self-image can turn into distorted fragments. However, there is evidence that a certain degree of personal identity can be retained.

How to support a person with dementia

Roles and relationships:

Dementia changes relationships with family and friends. Family responsibilities shift and those affected often have to accept a less active role. Psychological counselling for individual or families can help to accept changes and find new roles.

Support the ability to make decisions and look for ways to protect the person's rights. Empathy and understanding are crucial. Individual psychotherapy or support groups can help to accept change and find new roles.

Competence and independence:

As cognitive abilities decline, certain skills such as the ability to make decisions, consenting to treatment, driving, financial matters and household management deteriorate. This has an impact on personal autonomy and self-esteem. The restriction of skills harbors risks, but also requires the protection of the person and their social environment. Support with important activities, emphasizing resources and recognizing the skills and successes that have been retained can prove helpful.

Use the life story to support the person's self, e.g. through reminiscence therapy or a biography book.

Legal aspects:

As dementia progresses, the ability to make decisions in financial, health and personal matters decreases. People with mild to moderate dementia are often still able to make decisions. Inability to make decisions should only be assumed in cases of severe dementia. Assisted consent and support for decision-making are preferable to proxy consent.

Support decision-making ability and look for ways to protect the person's rights.

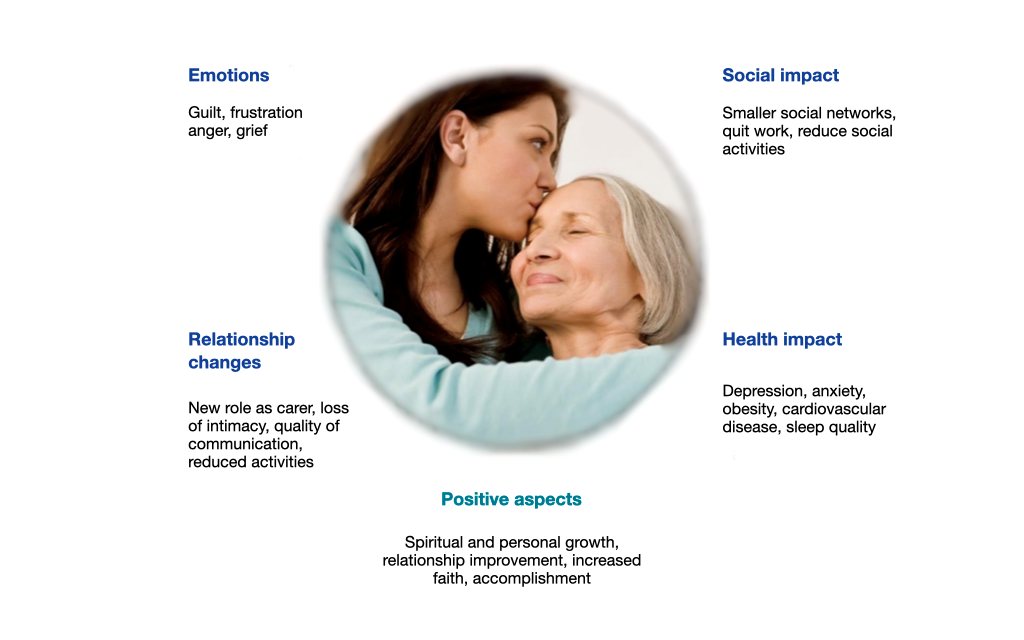

Impact on the family

Relatives of people with dementia are known to be particularly burdened by caring for them. They complain about feelings of being overwhelmed, lack of understanding, guilt and anger. They often take on the role of the main caregiver, which can lead to stress, isolation and financial problems.

Changes and conflicts:

The shifting of roles and responsibilities can lead to tensions in the family. Working caregivers may have to reduce or give up their employment, but often receive little support from their community.

Stress factors:

Women are more likely than men to be caregivers and therefore are usually more strained with burdens. Also health problems and difficult social relationships can be additional stress factors for family carers. Problematic behaviour of dementia patients, in particular depression, restlessness, aggression and listlessness, are the major sources of stress.

How to support the family of a person with dementia

Collaboration: Caring for a person with dementia requires a comprehensive plan that includes collaboration between medical professionals, other health and social care professionals and the family and loved ones. Seeking professional help can make care much easier and reduce the impact of dementia on the social environment.

Imparting knowledge and skills: Sufficient knowledge and appropriate skills about dementia, especially about symptoms, progression and dealing with challenging behavior are crucial for effective and sustainable care and support.

Support: Effective forms of support for caregiving relatives include psychoeducation, communication training, mindfulness training and stress management.

Examples

Peter has recently been diagnosed with dementia and is afraid of what happens when he will no longer be able to express his wishes and make decisions. With the help of a social worker he wrote down his preferences in an advance directives document.

Joseph encountered difficulties in his job at the bank because of the problems with attention and working memory. By talking to his supervisor, he managed to move to a quieter and less distracting place, change his working schedule, and later adopt a less demanding position.

Sabine felt overwhelmed by suddenly being the caregiver of her mother. In addition to unpleasant and unfamiliar emotions she struggled with uncertainty and lack of information. Specialists who explained the diagnosis and referred her to a caregiver support group helped her master the difficult situation.

References

- Baikie E. The impact of dementia on marital relationships. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. 2002;17(3):289-299.

- Brod M, Stewart AL, Sands L, Walton P. Conceptualization and measurement of quality of life in dementia: The dementia quality of life instrument (DQoL). Gerontologist. 1999; 39:2 5-35, 1999

- Brodaty H, Donkin M. Family caregivers of people with dementia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 11: 217-228, 2009

- Caddell LS, Clare L. The impact of dementia on self and identity: A systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev 30: 113-126, 2010

- Camp CJ. Denial of Human Rights: We must change the paradigm of dementia care. Clin Gerontol 42: 221-223, 2019.

- De Boer ME, Hertogh CMPM, Dröes RM, et al. Suffering from dementia - the patient`s perspective: a review of the literature. Int Psychogeriatr 19: 1021-1039, 2007

- El Haj M, Antoine P, Nandrino JL, Kapogiannis D. Autobiographical memory decline in Alzheimer’s disease, a theoretical and clinical overview. Ageing Res Rev 23: 183-192, 2015

- Feast A, Moniz-Cook E, Stoner C, Charlesworth G, Orrell M. A systematic review of the relationship between behavioral and psychological symptoms (BPSD) and caregiver well-being. Int Psychogeriatr 28: 1761-1774, 2016

- Frierson RL., Jacoby KA. Legal aspects of dementia. Handbook of Clinical Neurology 89: 107 – 113, 2008.

- Giebel CM, Sutcliffe C, Challis D. Activities of daily living and quality of life across different stages of dementia: A UK study. Aging Ment Health 19: 63-71, 2015

- Górska S, Forsyth K, Maciver D. Living With Dementia: A meta-synthesis of qualitative research on the lived experience. Gerontologist 58: e180-e196, 2018

- Hegde S, Ellajosyula R. Capacity issues and decision-making in dementia. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 19 (Suppl 1): S34-S39, 2016

- Martyr A, Nelis SM, Quinn C, et al. Living well with dementia: A systematic review and correlational meta-analysis of factors associated with quality of life, well-being and life satisfaction in people with dementia. Psychol Med 48: 2130-2139, 2018

- Müller T, Haberstroh J, Knebel M et al. Assessing capacity to consent to treatment with cholinesterase inhibitors in dementia using a specific and standardized version of the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool (MacCAT-T). Int Psychogeriatr 29: 333-343, 2017

- Nelis SM, Wu Y-T, Matthews FE, et al. The impact of co-morbidity on the quality of life of people with dementia: Findings from the IDEAL study. Age Ageing 48:3 61-367, 2019

- Nys H, Raeymaekers P, Gombault B, Rauws G. Rights, anutonomy and dignity of people with Dementia. Alzheimer Cooperative Valuation in Europe (ALCOVE) Deliverable no. 7. Fondation Roi Baudouin, September 2013 https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/chafea_pdb/assets/files/pdb/20102201/20102201_d7-01_en_ps.pdf

- Sanders S. Is the glass half empty or full? Reflections on strain and gain in cargivers of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. Soc Work Health Care 40: 57-73

- Schofield H, Bloch S. Family Caregivers: Disability, illness and ageing. Allen & Unwin; 1998

- Steeman E, de Casterlé BD, Godderis J, Grypdonck M. Living with early-stage dementia: A review of qualitative studies. J Adv Nurs 54: 722-738, 2006

- Thomas P, Chantoin-Merlet S, Hazif-Thomas C, et al. Complaints of informal caregivers providing home care for dementia patients: The Pixel study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 17: 1034-1047, 2002

- Woods RT, Nelis SM, Martyr A, et al. What contributes to a good quality of life in early dementia? Awareness and the QoL-AD: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 12: 94, 2014

- World Health Organization. Ensuring a human rights-based approach for people living with dementia. www.who.int/mental_health/neurology/dementia/en/